“You are one of countless

Whose story was never told

And never will

As all records were burnt.”

Birangona, Sadaf Saaz Siddiqui.

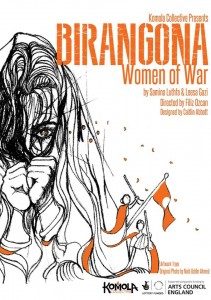

Dreadful, horrendous and devastating memories of the ‘70s are still alive with Moryam. Sitting in her Sirajganj cottage in Bangladesh, curls into herself Moryam does not want to recollect those days. With bleary eyes, she expressed her pain to Lisa Gazi, an actor from London who came in search of voices for her project “Birangona: Women of War”.

The nine-month-long struggle for Independence in Bangladesh had many repercussions. The Bengalis of then East Pakistan faced vigorous repressions by the majority, from denying the Bengali language national status to ruling them out from civil and military services.

Throughout history, war has been gendered, and its implications and consequences for women and men differ in terms of the nature of various injuries often leading to deaths.

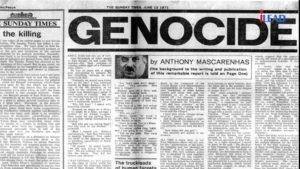

1971 was no exception. The war broke out on March 25 when West Pakistan began a military crackdown on then East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). Historians termed it “Operation Searchlight” but people of Bangladesh described it a villainous act by Pakistan.

Scores of people died. Many displaced due to famine and political unrest. In this world of “to be or not to be” people had witnessed genocide.

Women, regarded as carriers of culture whose bodies are symbols of the nation to be defended by men, are especially vulnerable in situations of battle, where their very identities as women come under threat. During the nine-month-long conflict the Pakistani army adopted a strategy of rape. On one hand there were an estimated 300,000 to three million people who were killed, on the other, 200,000–400,000 Bangladeshi women and girls were raped by the Pakistani army. Women and girls from the ages of seven to seventy-five were raped, gang-raped, and either killed or taken away by the military to become sex slaves to officers and soldiers for the duration of the war.

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (aka Mujib), Father of Bangladesh gave them a title, “Birangona” or war heroines to the women who were raped during the war by the Pakistani army; in an effort to respectfully reintegrate them back into society. Birangona is Bengali for “the brave ones.”

Soon after the war many rehabilitation centres were established to provide the women with medical aid, including treatment of diseases and abortion of unwanted pregnancies. The marry-off campaign was launched to encourage Bangladeshi men to come forward and marry the rape victims. The government started offering the women training in income-generating activities and other social support were given.

Bangladeshi men who married the rape victims though appreciated and were given economic support from the government, still the overall gesture failed.

Although these measures and the Birangona label overall, were presumably intended to honor the dishonored women and help them regain acceptance in a conservative, Muslim-majority society where a woman’s worth lay in her virtue and chastity, many rape-survivors declined to accept the title for fear of being stigmatized in the society. Still today, when people hear the horrific stories of Birangonas, it leaves indelible marks in their lives.

The Bengali word most often used, lanchhita, connotes numerous states, from disgraced, harassed, insulted, and persecuted to stained, tarnished, spotted, and soiled. In no way do these words contribute to the image of a “heroine”; they refer rather to people who have been shamed. Other words— biddhosto, meaning ruined or destroyed; bibhranto, meaning confused or bewildered; and phrases such as “women who have lost their all”— also portray a shattered image of someone who is supposed to be a heroine.

The whole idea of women having “lost their all” as a result of having been raped reinforces an already prevalent social norm— that a woman’s “all” lies in her virginity when she is unmarried, in her chastity when she is married, and in her sexual exclusivity in general. Had the media, without undermining the brutality of rape, placed less significance on sexual chastity and exclusivity in their presentation of the Birangona, the social ramifications after the event might have been reduced.

The media did not even take a critical role by questioning the government programmes or even providing any sort of feedback on them. They simply reiterated them.

Had the newspapers instead run in-depth interviews and stories, the birangona could have expressed their views on, for example, rehabilitation measures that would benefit them, the treatment of war babies, and the bringing of perpetrators to account. And most of all, this would have been an effective way for the women to have their voices heard.

Pritika Datta, Content Editor, iLEAD Publication, Kolkata.

Pritha Banerjee, Research Uptake Assistant, MS Swaminathan Research Foundation, Chennai. (Guest Author)